Scripture, Interpretation, and Joshua Hochschild

Note: This is in a sense an internal discussion in seminary, but I think everyone can gain something from it and please feel free to comment on my view!

There is always an inclination in evangelicalism (broadly defined, please) to bandy around the charge "That's not what the Bible says!" or to set up a opposition to "what the Church (Anglican, Roman, fill in the blank) teaches" and "what Scripture says." I think this perspective usualy betrays itself when someone frustratedly asks "Why can't we just get back to Scripture!?!"

Good question. We can't. But before you scream "relativist!" let me make it clear that we were never intended to "go back to Scripture" in the way this phrase claims. We aren't Muslims, we don't have some kind of original static divine speak in the Bible. If that were true we would all be learning Greek and Hebrew and even then we would never be sure about if we were right since our understanding of these ancient languages is not perfect. Check out a Greek concordance next time if you don't believe me. We as Christians believe that the Word of God is the inspired words of Scripture AS INTERPRETED BY HIS CHURCH. I think this bold part is essential and is the key to stearing clear of a lot of troubles. Let's look at this intepretation bit, then two examples of why it is important, and then get to the name in the title that you are all wondering about.

First, we shouldn't be scared of interpretation; we all do it all the time. There is nothing else in life, really. Just walking down the street today I was looking at cars - but I wasn't looking at cars as some detached object scientifically. I was looking at them AS moving things to be avoided. Looking out my window now I can look at a car AS something which collects rain, or AS something made of metal, or AS something I should key later. The important thing to notice is that I never look at "a car", I always look at a car AS something. My situtation, background, context, spiritual condition (yes!) all play a part in the Interpretive Framework in which I live and move. This is perfectly reasonable - we are embodied beings that are involved with the world around us. Dasein as being-in-the-world if you like Heidegger.

If you accept this (I can't imagine not accepting it once you think about it, really) then this should also apply to how we read Scripture. We always read it AS something: a source of doctrinal truth, a rule book on how to live life, a song to be sung, a poem to be awed by, etc. The possibilities are endless and that's what makes being a finite human so muke fun! We always move "further up and further in" as we meet God in Scripture, to quote C.S. Lewis (anyone know the reference?). But the important part here is that we are always interpreting Scripture within a framework. Let's make that clear: we never know Scripture as "plain Scripture", we only know and understand it inasmuch as we understand anything - within a certain framework which guides our understanding. Gadamer calls this "prejudice" in positive terms, Heidegger calls it "fore-understanding", I call it true.

What does this mean then? Well, it means that the claim "Scripture says" always has to be read as "Scripture, as I interpret it with _______ framework, says." Now this does not mean that Scripture can say anything you want it too truthfully; some frameworks have more claim to truth then others; but the essential point is we need to compare frameworks before we get to Scripture in heated debate. Roman Catholics are not "less" Scriptural than Protestants, they just interpret Scripture through a different hermeneutical key: the Magesterium. Protestants have their own hermeneutical key (well the best do, others are slaves to the newest wind of doctrine and misunderstanding) whether it is Westminster Confession, Luther's Works, 39 Articles and Prayer Book, whatever. Basically none of us comes to Scripture in a vacuum or free of an interpreted framework within which to read it; interpretative frameworks are essential to understanding itself! If you don't think you have an interpretive framework within which you read and understand Scripture there are only two possibilities: 1. You have a really shady and unexamined one (most likely), or 2. You are God.

Let's see how this works out in practice for a moment since theory gets boring (to some!). First an example from Church history, then a more recent version.

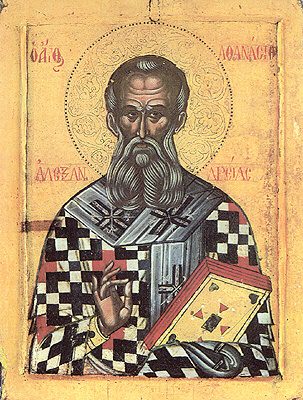

1. Arians! Okay, I imagine that everyone has a basic idea what these fellows said. Arius was a fourth century Bishop (!) who taught that Jesus was not of the same substance as God the Father, basically that God was the Uncreate, Jesus was first among creatures, still divine, but "unlike" the Father. Athanasius (a young deacon - who said they weren't important!) established the orthodox position at the Council of Nicea in 325. More than the historical struggle what interests me is why Arius was wrong. One of the things that he had going for him was that he took Scripture more "literally" than Athanasius did. He was fine with affirming Jesus as divine Son of God, more than humans and before the world existed; but he also took the Son terminology seriously and insisted that "there was a time when the Son was not." Athanasius and orthodoxy defended the co-eternality of Son and Father, but they did so with philosophical arguments rather than "Scripture alone." In fact, I don't think Scripture has a whole lot to say in any direct fashion about the eternal generation of the Son which orthodox Christians believe. So why did Athanasius triumph? Because the Church decided that his view was the best way to interpret the Scripture, even though it was not as "literal" as Arius and led to serious mysteries which Arius did not have. The Greek framework of Athanasius (and Gregory of Nyssa) beat out the Gnostic framework of Arius, even though his "made more Scriptural sense." So if you affirm the Athanasian position (and to be orthodox, you must) you have to realize that interpretive frameworks are essential in understanding Scripture; we can not do without them and would be in bad shape if we tried.

2. Jesus as Lord. To give a more modern interpretive example, take the statement: "Jesus is Lord (Romans 10.9)." What does that mean? Well, it depends on what framework you are using. The standard answer (?) is that Jesus is LORD in the Jewish God sense, or at least there is some claim to divinity and supremacy in this claim. Tom Wright however seem to think Paul was using it as a political polemic, as in "Jesus is Lord means Caesar is not!" My first inclination is to see it saying Jesus is Cosmic Lord as in providential control of the universe. Other people would see it as saying Jesus is Lord as ruler of my life choices. Which one is correct? Well, they all are! All of them are perfectly in line with Scriptural witness to Jesus and can fill out the meaning when Paul uses it. Did he have them all in his mind (or any of them?) when he wrote? Doubtful. Does that mean that I need to figure out what Paul thought in order to say I understand what "Jesus is Lord" means? Of course not! But I do need to realize that I understand it from within a particular framework, not in a vacuum. But we are doing this everytime we read and understand Scripture, so there is no problem.

Final Point: what I am saying here has almost nothing to to with the Roman Catholic discussion of Scripture vs. Tradition. The Protestant understanding of that is so muddled it would take a bunch of posts to get it clear! Everything I have been saying has kept only to the Scriptural principle echoed in the Reformation: sola Scriptura! There is no Scripture outside of interpretation, although some claim there is Tradition outside of Scripture (I am not so convinced, but enough for now). This has been a recent news event when Wheaton released their Medieval philosophy professor, Josh Hochschild, for converting to Roman Catholicism. Wheaton requires every faculty member to sign a statement of belief that includes sola Scriptura but when Dr. Hochschild signed it openly affirming the principle the college said he was not allowed to continue on. Wheaton is right in being able to release professors, but in this case the reason for release was his Roman Catholicism, not his inability to sign the statement! He could openly affirm sola Scriptura in the sense above because we all must if we understand what we do when we read Scripture.

So to sum up, this does not mean that God's word is falliable and that anything goes; it means that as Christians we trust God to enable his Church through the Holy Spirit to interpret Scripture faithfully.